LBJ Launched the Great Society 50 Years Ago

|

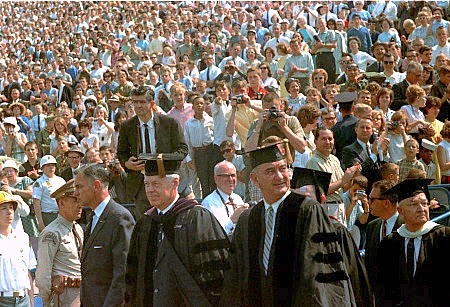

| President Lyndon Johnson at the University of Michigan, where he delivered a commencement speech six months after assuming office following President Kennedy's assassination. |

As we focus our attention this Spring of 2014 on the challenges facing those graduating seniors who are taking part in college commencement exercises around the country, let us pause and consider a commencement that took place fifty years ago. This one occurred on May 22, 1964, at Michigan Stadium, one of the largest athletic venues in the world, on the campus of the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. The speaker that day was a man whose political stature and ambition matched the physical surroundings, President Lyndon Johnson. I would assume that many present that day were harboring some feelings of sadness and regret because the person who had originally been invited to speak at the commencement was the late President John F. Kennedy. But, the events in Dallas exactly six months earlier, had, unfortunately, caused a change in plans. Although he was not known for his oratorical skills, the new President rose to the occasion and made the day memorable. In an address that lasted a little over eighteen minutes, Johnson, employing striking rhetoric and heroic allusions, seized the opportunity to lay out a domestic policy agenda he thought the United States should undertake during the 1960s. He called his agenda “The Great Society.”

Theodore Roosevelt, a Republican, was the first U.S. President to use a catchphrase—“the Square Deal”—to describe his domestic program. Subsequently, however, such catchphrases became the purview of Democratic chief executives beginning with Woodrow Wilson’s “New Freedom,” followed by Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal,” Harry Truman’s “Fair Deal,” and the “New Frontier” of John F. Kennedy. Lyndon Johnson’s beloved mentor was FDR, and Johnson saw the “Great Society” as a fulfillment and advancement of Roosevelt’s progressive policies of the 1930s that sought to alleviate the harsh effects of a capricious, depressed economy. The words expressed by Johnson in the Ann Arbor speech, although inspiring, offered only a mere outline of the ideas he, and his aides, were developing to carry on Roosevelt’s legacy and assuage the problems they saw confronting America in the 60s. Speaking in broad terms, Johnson identified five such problems that day—poverty, race relations, urban decay, environmental degradation, and education opportunity.

No one who witnessed the speech could have foreseen the enormous energy that Johnson summoned within the next year to turn those broad ideas into practical policy measures. Throughout the rest of 1964 and into 1965 and 1966, the Johnson administration inundated Congress with a plethora of legislation aimed at bringing the federal government’s weight to bear on the social ills that were mentioned that day in Ann Arbor. What is so impressive about Johnson’s efforts in those years was that not only was he able to introduce such a significant amount of legislation, he was also successful in getting Congress to pass it. Among the major laws enacted by Congress during Johnson’s presidency were the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, the Food Stamp Act of 1964, the Wilderness Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, the Social Security Act of 1965, the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965, the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965, and the Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1965.

Looking back on that time, one of the most striking aspects one sees of the “Great Society” was that, in contrast to other progressive policy agendas that came before it, LBJ’s efforts were aimed not just at creating greater opportunities for the nation’s underclass but also at protecting and improving the lives of the middle class as well. So, in addition to the many “War on Poverty” measures that were enacted, the era also witnessed the creation of programs and institutions whose purpose was to help promote the arts, culture, the natural and built environments, public safety, and the rights of the consumer. The National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, National Public Radio, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration are a few of the examples of the Great Society’s lasting legacy.

President Johnson’s speech can be read, viewed, and listened to at the websites of both the LBJ Presidential Library and the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan. The text of that speech, and all other public statements made by President Johnson, can also be read in hard copy by consulting the multi-volume Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, Lyndon B. Johnson, which is housed in the Government Documents Department at the Birmingham Public Library.

For those wanting to read more about Lyndon Johnson and his presidency, there are numerous books available at the Birmingham Public Library and elsewhere in the JCLC system. Certainly the most comprehensive, but still unfinished, is Robert A. Caro’s multivolume, The Years of Lyndon Johnson. Historian Robert Dallek’s studies of Johnson’s life have also received critical acclaim, including Lone Star Rising: Lyndon Johnson and His Times, 1908-1960, Flawed Giant : Lyndon Johnson and His Times, 1961-1973, and Lyndon B. Johnson : Portrait of a President. Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream is considered to be a classic portrait written by Doris Kearns Goodwin, who spent many hours interviewing the former president during the last years of his life. Irwin Unger’s The Best of Intentions: The Triumph and Failure of the Great Society Under Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon provides an interesting examination of the politics and policy concerns that shaped LBJ’s agenda.

Jim Murray

Business, Science & Technology Department

Central Library

Comments