Birmingham at 150—Part 3

(In the interest of brevity, this section provides only an overview. Additional online BPL resources are listed at the end of this article)

The story of the Civil Rights movement is a difficult one to tell.

It is filled with gratuitous violence and painful truths. It is uncomfortable for me to discuss as a white man whose family comes from Birmingham. I am under no illusion as to which side my grandparents and great-grandparents stood on as it was happening.

Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, responding on what he would like to do to Bull Connor if he had his way, said:

I would like the day to come when Mr. Connor and I and others can just sit down and talk like men to men, women to women and people to people1.

If we as residents of Birmingham continue to move forward, then we must overcome our reticence to speak. We must tell the uncomfortable stories out loud lest we forget just how horrible and recent it all was.

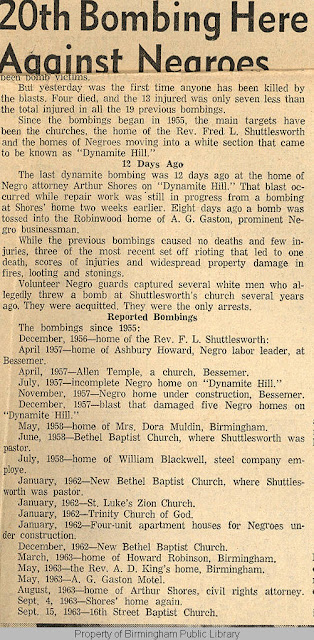

By the 1950s, the state of the city could no longer be ignored. Segregation, lynchings, bombings: Birmingham was a city of state-sponsored violence against its black residents2.

Over the next 20 years, the racist practices of the City of Birmingham and the State of Alabama were challenged from within and without.

The federal government tried to legislate integration, but the white ruling class in Alabama showed no willingness to enforce federal laws.

On May 17, 1954, the federal government issued its landmark ruling in Brown Vs. The Board of Education that made integrated school districts the law of the land.

Not that this meant anything to men like Bull Connor. Tensions inflamed as politicians statewide dug in their heels against what they saw as overreaching by the federal government.

In response to the rising tempest, brave men and women in the black community organized. In 1956, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth created the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights—one of the first and most influential organizations of its kind in the state.

For more than a decade, Shuttlesworth and the ACMA were on the front lines of The Civil Rights Movement, a position that did not come without significant danger.

The ACMA focused its efforts on integrating busses, businesses, and schools and for equal voting rights. They were a non-violent organization, staging sit-ins, protests, and holding themselves calmly in solidarity even as they were met with violence and hatred.

For his part in organizing and leading, Shuttlesworth became a target3. He was arrested multiple times, his house was bombed, and he was beaten while trying to enroll his daughters at an all-white school.

By 1960, it had become clear that no amount of rhetoric would ever persuade the leadership or the white population of Birmingham to extend equal rights to black citizens.

Every attempt at peaceful conversation was met with violence and intimidation. Houses of black activists were destroyed. Protestors were beaten and arrested. White politicians bent over backward to maintain the status quo, going so far as shutting down all city parks and recreation centers rather than face the prospect of offering equality to their fellow citizens.

In 1961, a group of students and activists set off on the Freedom Rides in an attempt to desegregate the bus system in the south4. When the bus stopped in Birmingham, the protestors were beaten indiscriminately as members of the Birmingham Police Department stood at a distance and looked on.

Facing a court order to integrate parks and swimming pools in 1962, the city chose to shut all city parks down instead. After an internal power struggle, Birmingham formed a new government, and Albert Boutwell defeated Bull Connor in a mayoral run-off.

The tumult in the city continued with both men claiming to be the rightful leaders of Birmingham.

In the spring of 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. made a series of speeches at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. Activated by his words and actions, students from the historically black Miles College organized sit-ins and protests intending to integrate the Birmingham Public Library5.

Wyatt Walker, who was the head of the Birmingham chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), recruited a fair-skinned black woman named Addine "Deenie" Drew to sneak into the library and take note of the exits and layout6.

Despite being mortally afraid, Deenie accepted the task. Later she would say that during that ordeal, she had to "look down at my feet and tell them to keep walking."

On April 9, she returned with several other black students who sat in the library and read. When head librarian Fant Thornly took no action, they left.

The next day more black students returned, but this time with Shelley Millender, another student at Miles College chosen to act as their spokesman. After a heated verbal exchange, the police were called.

But seeing that Walker tipped off several reporters to the situation and fearing another national spectacle, they refused to arrest the black patrons.

Thornly, seeing the writing on the wall, called an emergency board meeting and proposed that the Birmingham Public Library (BPL) system integrate immediately to avoid further national embarrassment.

Simultaneously, Shuttlesworth, Martin Luther King Jr., and Rev. Ralph Abernathy launched the Birmingham Campaign, a series of protests aimed at drawing attention to the cause and further exposing the city nationally for its abusive treatment of black citizens7.

Just three days after the integration of the library, King was arrested and jailed for nine days, biding his time in that prison cell by writing his famous Letter from a Birmingham Jail.

The next month and a half was the most tumultuous time in Birmingham's history. Thousands of black citizens were arrested for protesting. Black children marching peacefully had police dogs and fire hoses turned on them.

All of this violence was broadcast to a national audience.

On September 15, 1963, the 16th Street Baptist Church was bombed with children inside8. Congress passed The Civil Rights Act of 1964 in response, but the bombings and lynchings continued in Birmingham.

But Birmingham was no outlier.

While struggles in other parts of the country received less media attention, Birmingham served as a barometer in many ways for the entire nation.

On the state of Birmingham in the sixties, James Baldwin said:

White people....don't want to believe, still less to act on that belief, that what is happening in Birmingham is happening all over the country9.

Of course, all of this history is still being written. The Civil Rights Movement of the sixties wasn’t the end or anything.

At its most hopeful, it was the crank of an engine on a cold February morning—the chug, chug, chug ignition scattering ice crystals and breaking the deceptive silence of an inert winter’s day.

The struggle didn’t end at 16th Street Baptist Church or with Bonita Carter or EJ Bradford or “[insert name here]10," and it won’t end until we as citizens of Birmingham choose to write a different story.

Continued in Part 4. Follow the BPL on Facebook (Meta), Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn to see more updates on this story.

Additional Resources

- BPL Archivist Reviews Book on Birmingham Children's March (bplolinenews.blogspot.com)

- Birmingham Public Library: Black Firsts in Birmingham (bplonline.org)

- Angry police sift blast clues; judge decries mockery of law - Newspaper Clippings - Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections (oclc.org)

- Arrest Record in Archives | This is a photo of a City of Bir… | Flickr

- Segregation Magazine and Newspaper Articles, Januay 1963 - Theophilus Eugene Bull Connor Papers, 1959-1963 - Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections (oclc.org)

- Letter to Bull Connor | This letter is part of the Theophilu… | Flickr

- John Lewis in Birmingham (bplolinenews.blogspot.com)

- White clergymen urge local Negroes to withdraw from demonstrations - Newspaper Clippings - Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections (oclc.org)

- Two negroes shot to death after bombing - Newspaper Clippings - Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections (oclc.org)

- Screams echo among debris - Newspaper Clippings - Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections (oclc.org)

By Caleb Calhoun | Library Assistant Ⅱ, Powderly Branch Library

1 White, Marjorie Longenecker, and Andrew Michael Manis. 2000. Birmingham Revolutionaries. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press. Pp. 76,77↩

2 Wright, Barnett, and Nicholas Patterson. 2013. 1963. Birmingham, AL: Birmingham News Company.↩

3 Patterson, Nick. 2014. Birmingham Foot Soldiers.↩

4 Bausum, Ann, John Lewis, and Jim Zwerg. 2006. Freedom Riders. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic.↩

5 Wiegand, Wayne. 2018. The Desegregation Of Public Libraries In The Jim Crow South. 1st ed. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.↩

6 Olson, Lynne. 2002. Freedom's Daughters. New York: Simon & Schuster.↩

7 Abernathy, Donzaleigh. 2003. Partners To History. New York: Crown Publishers.↩

8 Smith, Petric J. 1994. Long Time Coming. Birmingham, Ala.: Crane Hill.↩

9 Peck, Raoul, and James Baldwin. 2016. I Am Not Your Negro. DVD. Velvet Film.↩

10 Jones, Ashley M. 2021. Reparations Now!. La Vergne: Hub City Press.↩

Comments