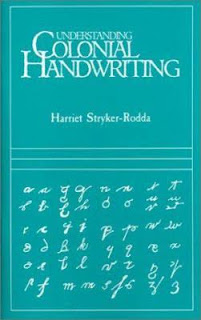

Southern History Book of the Month: Understanding Colonial Handwriting

Understanding Colonial Handwriting

Harriet Stryker-Rodda

Does anyone remember penmanship lessons in elementary school? I can recall having to sit in a certain position, holding the pen just so, shaping the Palmer Method letters . . . then thankfully abandoning the whole process the minute class was over and going back to my usual chicken scratch. Deciphering another person’s handwriting can be a challenge even in this century, but genealogical researchers can encounter real difficulties when they examine documents from centuries past. The letters of the alphabet, no matter how carefully shaped, can often be completely different from the current versions. This is when researchers can be grateful for a brief but helpful guide like Understanding Colonial Handwriting when consulting original documents. As Stryker-Rodda points out, more and more material is available online but as transcription errors creep in over time, it becomes necessary to check the original source for accurate information:

Recourse to original records, in whatever form, assures the researcher that no one has tampered with the content or the physical construction of the record. The changing styles of letter formation and the condition of the paper may present problems to the uninitiated. To analyze such a document we must understand its history, its purpose, its tools, even its scribe and his manner of writing.

The mention of tools caught my attention—how often do we even now refer to a sort of small knife as a “pen knife” without remember that its original purpose was for trimming a quill pen?

For all its brevity (less than 30 pages), this pamphlet covers a lot of research territory related to the transcription of colonel documents: how the use of a quill pen affected the formation of lettering, idiosyncrasies of punctuation, comparisons of American and English handwriting styles, the lack of standardized spelling, interchangeable letters such as I and J or U and V, and the long s that looks more like an f. There is also the reminder that “when we consult a colonial document we see a miracle of survival . . . it has survived the vicissitudes of war, vermin, weather, and human neglect.” The family historian can be grateful for every centuries-old document that still exists, and equally thankful for every guide that can help in figuring out what it says. Understanding Colonial Handwriting is a handy portable guide for the researcher and is readily available through vendors such as Genealogical Publishing. For more on this topic, there are some lengthier guides in the Southern History Department:

How to Read the Handwriting and Records of Early America

Reading Early American Handwriting

Good luck in your research, and happy deciphering!

Mary Anne Ellis

Southern History Department

Central Library

Harriet Stryker-Rodda

Does anyone remember penmanship lessons in elementary school? I can recall having to sit in a certain position, holding the pen just so, shaping the Palmer Method letters . . . then thankfully abandoning the whole process the minute class was over and going back to my usual chicken scratch. Deciphering another person’s handwriting can be a challenge even in this century, but genealogical researchers can encounter real difficulties when they examine documents from centuries past. The letters of the alphabet, no matter how carefully shaped, can often be completely different from the current versions. This is when researchers can be grateful for a brief but helpful guide like Understanding Colonial Handwriting when consulting original documents. As Stryker-Rodda points out, more and more material is available online but as transcription errors creep in over time, it becomes necessary to check the original source for accurate information:

Recourse to original records, in whatever form, assures the researcher that no one has tampered with the content or the physical construction of the record. The changing styles of letter formation and the condition of the paper may present problems to the uninitiated. To analyze such a document we must understand its history, its purpose, its tools, even its scribe and his manner of writing.

The mention of tools caught my attention—how often do we even now refer to a sort of small knife as a “pen knife” without remember that its original purpose was for trimming a quill pen?

For all its brevity (less than 30 pages), this pamphlet covers a lot of research territory related to the transcription of colonel documents: how the use of a quill pen affected the formation of lettering, idiosyncrasies of punctuation, comparisons of American and English handwriting styles, the lack of standardized spelling, interchangeable letters such as I and J or U and V, and the long s that looks more like an f. There is also the reminder that “when we consult a colonial document we see a miracle of survival . . . it has survived the vicissitudes of war, vermin, weather, and human neglect.” The family historian can be grateful for every centuries-old document that still exists, and equally thankful for every guide that can help in figuring out what it says. Understanding Colonial Handwriting is a handy portable guide for the researcher and is readily available through vendors such as Genealogical Publishing. For more on this topic, there are some lengthier guides in the Southern History Department:

How to Read the Handwriting and Records of Early America

Reading Early American Handwriting

Good luck in your research, and happy deciphering!

Mary Anne Ellis

Southern History Department

Central Library

Comments