Book Review: Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer

by Richard Grooms, Fiction Department, Central Library

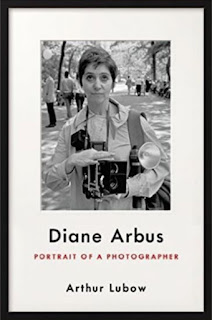

Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer

Arthur Lubow

I’ve been fascinated by Diane Arbus for decades, but I’ve long been frustrated by the fact that a first-rate biography has never come out. When Arthur Lubow’s account surfaced in 2016, I had hopes that this might be it. It took some review reading and some attempts at immersing into it to realize that this was in fact the biography I’d been waiting for. I’d always wondered how a sheltered young New York woman from a rich family ended up taking portraits of those on society’s margins—street kids, homosexuals, transvestites, circus and sideshow performers, mental patients and so on-in the '50s and early '60s when such people were held at arms’ length by the mainstream, and were considered “freaks,” the consensus term of that time. Diane was the one that photographed freaks, they said. Some said she exploited them. But her pictures of these, and plenty of more conventional people, would propel her into the limelight and help transform photography from documentation and craft into art. That we talk of photography today matter-of-factly as an art form is due in no small measure to her.

Diane Arbus was always different. Despite the cosseting of her family, she dated mostly guys her parents disapproved of and married one of them at an early age, foregoing college and economic security. With her husband Allan Arbus, she got a solid grounding in picture taking, leaving him in the late '50s to become a single mother and freelancer. Curiously, she always had a fraught relationship with mechanical objects. Paradoxically, this somehow became a strength, freeing her to use cameras in ways her peers seldom did. Though very ambitious, she accepted her quirks and drawbacks and channeled them into her work. Instead of quitting when fear arose, she plowed ahead and realized that however weird her portrait subjects might seem, actually meeting and getting to know them was easier than the initial decision to pursue them. She had enormous charm, a little girl personality that was readily available and an ability to make anyone comfortable. She could make almost anyone drop their guard, their public mask.

It’s amazing now to read about anyone, especially a single woman, making it as an artist in New York City. Though Diane did get financial help from Allan after she left him (and would occasionally get handouts from her parents), she largely supported herself and two daughters. You could do that in New York in those days. Bohemia hadn’t been economically wiped out of Manhattan. But Lubow always reminds us of what a grind it was, how little photography paid then, how many editors nixed her pictures. And you want to see all of them, no matter how mediocre they might have been.

It’s nothing short of astonishing that Lubow has been able to uncover the wealth of data he has when you realize that, since Diane Arbus’ death in the early '70s, her daughter Doon has built a virtual blockade around her estate. It’s because of this that no Arbus photos are in the book (though there are photos of Arbus, family, friends, and lovers). A table of Photographs Discussed In The Text is in the start of the book. Unfortunately, the list only covers about 80% or so of the photos discussed in the book. This is the only significant problem with the book. The thing to do is get a copy of Revelations by Diane Arbus, a posthumous collection of her photos that surpasses all other collections. If you’re even moderately interested in Arbus, you’ll want to look up the photos as you read this book. Lubow is excellent at making you want to do so, and look again at the pictures you thought you knew. He helped me to see new aspects of familiar photos (even ones I thought I couldn’t see anew anymore) and ably introduced me to not-so-familiar ones. Arbus was a genius at capturing the right details, and Lubow gets us to notice these.

One reason Arbus is key is because she broadened our view of American people. She brought into her fold individuals who’d previously been considered unfit to see or acknowledge. She made them her friends. Not her inner circle of friends, but friends nonetheless. She let them look at us through her pictures, and this helped at least some to realize that these were people of worth. She portrayed them not as noble, without sentimentality or condescension. They were what they were. That was enough. That was a very brave thing to do. She nearly always got them right. There’s something very admirable and courageous about this, but Arbus was very far from saintly. She had many flaws, and Lubow catalogs them, shows how they compromised her, dragged her down. It wasn’t all marginals, though. She often photographed well-known politicians, celebrities, and scene makers too. She could uncover hidden truths in most all of her subjects, and it sometimes (perhaps regularly) happened that her subjects regretted letting her take their picture. She didn’t recognized boundaries or taboos. She moved the hidden into the light, even with the well-known. Lubow sympathetically (but not uncritically) shows us how she did it all this. America is always a lot larger and more diverse than we think it is, or that we’re willing to admit, and Arbus is one of those pathbreakers that helped us see this.

Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer

Arthur Lubow

I’ve been fascinated by Diane Arbus for decades, but I’ve long been frustrated by the fact that a first-rate biography has never come out. When Arthur Lubow’s account surfaced in 2016, I had hopes that this might be it. It took some review reading and some attempts at immersing into it to realize that this was in fact the biography I’d been waiting for. I’d always wondered how a sheltered young New York woman from a rich family ended up taking portraits of those on society’s margins—street kids, homosexuals, transvestites, circus and sideshow performers, mental patients and so on-in the '50s and early '60s when such people were held at arms’ length by the mainstream, and were considered “freaks,” the consensus term of that time. Diane was the one that photographed freaks, they said. Some said she exploited them. But her pictures of these, and plenty of more conventional people, would propel her into the limelight and help transform photography from documentation and craft into art. That we talk of photography today matter-of-factly as an art form is due in no small measure to her.

Diane Arbus was always different. Despite the cosseting of her family, she dated mostly guys her parents disapproved of and married one of them at an early age, foregoing college and economic security. With her husband Allan Arbus, she got a solid grounding in picture taking, leaving him in the late '50s to become a single mother and freelancer. Curiously, she always had a fraught relationship with mechanical objects. Paradoxically, this somehow became a strength, freeing her to use cameras in ways her peers seldom did. Though very ambitious, she accepted her quirks and drawbacks and channeled them into her work. Instead of quitting when fear arose, she plowed ahead and realized that however weird her portrait subjects might seem, actually meeting and getting to know them was easier than the initial decision to pursue them. She had enormous charm, a little girl personality that was readily available and an ability to make anyone comfortable. She could make almost anyone drop their guard, their public mask.

It’s amazing now to read about anyone, especially a single woman, making it as an artist in New York City. Though Diane did get financial help from Allan after she left him (and would occasionally get handouts from her parents), she largely supported herself and two daughters. You could do that in New York in those days. Bohemia hadn’t been economically wiped out of Manhattan. But Lubow always reminds us of what a grind it was, how little photography paid then, how many editors nixed her pictures. And you want to see all of them, no matter how mediocre they might have been.

It’s nothing short of astonishing that Lubow has been able to uncover the wealth of data he has when you realize that, since Diane Arbus’ death in the early '70s, her daughter Doon has built a virtual blockade around her estate. It’s because of this that no Arbus photos are in the book (though there are photos of Arbus, family, friends, and lovers). A table of Photographs Discussed In The Text is in the start of the book. Unfortunately, the list only covers about 80% or so of the photos discussed in the book. This is the only significant problem with the book. The thing to do is get a copy of Revelations by Diane Arbus, a posthumous collection of her photos that surpasses all other collections. If you’re even moderately interested in Arbus, you’ll want to look up the photos as you read this book. Lubow is excellent at making you want to do so, and look again at the pictures you thought you knew. He helped me to see new aspects of familiar photos (even ones I thought I couldn’t see anew anymore) and ably introduced me to not-so-familiar ones. Arbus was a genius at capturing the right details, and Lubow gets us to notice these.

One reason Arbus is key is because she broadened our view of American people. She brought into her fold individuals who’d previously been considered unfit to see or acknowledge. She made them her friends. Not her inner circle of friends, but friends nonetheless. She let them look at us through her pictures, and this helped at least some to realize that these were people of worth. She portrayed them not as noble, without sentimentality or condescension. They were what they were. That was enough. That was a very brave thing to do. She nearly always got them right. There’s something very admirable and courageous about this, but Arbus was very far from saintly. She had many flaws, and Lubow catalogs them, shows how they compromised her, dragged her down. It wasn’t all marginals, though. She often photographed well-known politicians, celebrities, and scene makers too. She could uncover hidden truths in most all of her subjects, and it sometimes (perhaps regularly) happened that her subjects regretted letting her take their picture. She didn’t recognized boundaries or taboos. She moved the hidden into the light, even with the well-known. Lubow sympathetically (but not uncritically) shows us how she did it all this. America is always a lot larger and more diverse than we think it is, or that we’re willing to admit, and Arbus is one of those pathbreakers that helped us see this.

Comments