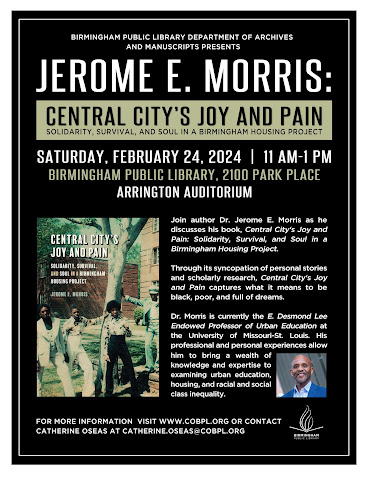

Central Library to Host Talk on Saturday, February 24, by Jerome Morris, Author of "Central City's Joy and Pain"

|

| Birmingham native Dr. Jerome Morris will speak about his book "Central City's Joy and Pain" and sign copies at the Central Library's Arrington Auditorium at 11:00 a.m. on Saturday, February 24. |

.jpg)

Birmingham, Ala. - Jerome E. Morris refused to let humble beginnings in a downtown Birmingham housing project deter him from achieving success in life.

Now a professor of urban education at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, Dr. Morris lived in a downtown subsidized housing community known as Central City before being renamed Metropolitan Gardens. His new memoir, "Central City's Joy and Pain: Solidarity, Survival, and Soul in a Birmingham Housing Project" shares Dr. Morris' personal story of survival to achieve personal success.

Dr. Morris will talk about his book and how he overcame odds in an author talk from 11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. this Saturday, February 24, in the Central Library's Arrington Auditorium, 2100 Park Place. The talk is presented by the Birmingham Public Library's Department of Archives and Manuscripts.

In a Q&A with BPL PR Director Roy Williams, who covered crime in what was then known as Metropolitan Gardens from 1990-1992 as a Birmingham News police reporter, Dr. Morris talked about what inspired the book and how he overcame odds.

BPL: What inspired you to write this book?

Dr. Morris: In Central City's Joy and Pain, I wanted to talk about the Birmingham post-civil rights, Birmingham beyond the 1963 church bombing and children's crusade. I wanted to show those of us who came out of the slums of Birmingham to achieve success, those whose stories rarely get talked about. The public needs to hear their stories too - Titusville, College Hills, and people who came out of the housing projects of Birmingham. The media today focus on the negative stories.

In this book I am showing these are the same African people who were on those plantations, these are the same people who fought for our civil rights, these are the same people that media still neglect. I am bringing light to their story. I wanted to bring light to the people who are incarcerated. Even though we grew up in poverty in Central City, we survived. The government has given up on people living in public housing today and people are having to fend for themselves.

I wanted to take the reader through my experience and show how we overcame. It represents a microcosm of the larger experience of our people and people all over the world who experience similar kinds of situations.

BPL: The book title "Central City's Joy and Pain" illustrates that you had both good and bad times growing up there. Elaborate.

Dr. Morris: The title comes from the Frankie Beverly song "Joy and Pain." We experienced joy and pain, like sunshine and rain as the song says. We always played Frankie Beverly and Maze in the house when I was growing up. I want the readers to say even though people grew up in dire circumstances, they loved each other. They want their children to do well. They were respectful when I grew up.

People mourned when they tore down those public houses of Metropolitan Gardens to build the new community Park Place. I wanted to bring a name to those people often neglected. There was that joy, there was that pain. The first chapter of the book is called "The Poorest Zip Code in America." They were using that term to describe our community whey they argued about tearing the area down. When i was growing up there was a 70 to 72 percent poverty rate.

The pain came not from the people but the circumstances. You were raising people in an area where they wondered why things always seemed to be bad. You are trying to raise a family in that environment. I want our people, black folks in Central City and places like it, to not look at failures, but people who were successful as well. I saw brilliant people in Central City. I did see brilliant people not become capable of what they could because opportunities were lacking.

I was a beneficiary of some opportunities. Everybody won't die, some of us will make it. There were other people who went to church everyday but still struggled. We have to create opportunities for people and cannot pray people into opportunities without sharing resources that were built on the backs of our ancestors. A lot of this nation's wealth was built on the backs of free labor by our ancestors. They kept our people from getting an education and jobs that create opportunities. But we are like a Phoenix, black folks are gonna rise.

BPL: The book subtitle, "Solidarity, Survival and Soul" is intriguing to me as well. Do you share stories of solidarity, survival and soul in the book?

Dr. Morris: Yes I do but I want to reader to be surprised and find out for themselves. The solidarity peace is that we came together as a community. We lived by the African proverb that it takes a village to raise a child. I was raised not just by my momma but my aunts, grandmothers, older brothers, older black men in the neighborhood, and coaches in particular when I played football.

The survival piece is we were already behind the eight ball by the situation we were in. We were in survival mode particularly due to economics in which people lashed out against themselves. When you ask what is wrong with these young folks, change their conditions, change their environment. Give them opportunities. Survival is what we were doing. It represents the soul of black folks.

BPL: I am almost 60. In our generation years ago, communities knew and supported each other. When a kid did wrong, adults spoke up. Today's generation you cannot say nothing to these kids. We don't have that village mentality we had back in the day why is that?

Dr. Morris: I am glad you used the word village because were a village in our communities. I interviewed approximately 40 people for this book. You learn about Central City through my lens but I highlight various people - It is their story through Jerome. Why is this notion of lack of community?

A lot of it has to do with closing schools in our communities. When you close down schools and don't have as many active churches with the presence we used to have, our communities believed in sticking together. That galvanizing force to come together plus faith held us together. We had pride as a people.

Back then in our music, in our language there was a notion of loving one another. There was affirmation of us as a people from James Brown to Marvin Gay to Aretha Franklin. We heard that in music and saw that in language like hey my brother, hey my sister. We came at other people through love and then moved into the American mainstream of it's all about the almighty dollar.

BPL: Did your background growing up in public housing inspire you to become a professor specializing in urban education?

Dr. Morris: Yes, it is my duty to bring the collective story of how ewe made it to the forefront. This is a story about a community of people, not about Jerome Morris. I came from those people and we can have that if we provide opportunities like I had growing up. I always wanted to do something for our community. I played football as an all-state quarterback at Philips High School. I was voted offensive player of the year by the Birmingham News my senior year. I was Salutatorian of my senior class.

I realized as I matured and went to college, I heard a political science professor talk about politics. I thought of various fields from civil rights law to politics. I knew I wanted to be a part of helping create healthy, vibrant black experiences and help others realize that greatness lies within.

BPL: Talk about how your success both on the football field as a quarterback yet in the classroom help counter stereotypes about black athletes. You were on honor society at Phillips High & graduated as Salutatorian in addition to being all-state quarterback, and in college at Austin Peay State you not only played quarterback but received the Governor's Award as top graduating male in the senior class.

Dr. Morris: When you look at a lot of black schools, a lot of the top students like Paul Roberson throughout history including scientists and singers were model athletes as well. That is a model we need to aspire to bring back. We are great in a lot of areas beyond sports. I could play great football, but showed I could be one of the top students academically in the school. The mainstream society only wants to black athlete. The thinker is the mind. People think you have to leave one of them behind. I was a thinking quarterback with awareness of what was going on. I became president of the African American Student Government Association and my fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha while in college. I was in the Student Government Association while playing quarterback.

BPL: What message do you hope readers of the book and attendees of Saturday's talk get from your presentation?

Dr. Morris: There is the message of the soul of a people. We gotta keep that. We must understand that the people experiencing some of these circumstances I want you to know there are some things aligned against you but you can overcome them. Don't dwell on that. People with privilege have hundreds of opportunities. For black people born into poverty, if you have one bad choice it can ruin you. That is not the way it should be. We need to create more options for people. Public housing is not bad, people vilify it. When done right, if we create great public housing and great schools you create opportunities for people to move out of poverty.

Comments