Researching Critical Race Theory at the Birmingham Public Library

|

| Learn more with the Birmingham Public Library. Photo by Parker Evans. |

In the last year or so, Critical Race Theory (or CRT) has headlined the news and emerged as a subject of political discussion around the country.

As of June 15, 2021, mentions of Critical Race Theory on Fox News shot up—1,900 mentions in 3.5 months. This fevered reaction to blatant misuse of the term has spread to Alabama as well.

Locally, a campaign ad for Kay Ivey reads, “No critical race theory in schools. America is not a racist nation. We won’t teach our children differently in Alabama.”

Earlier this month, Alabama Superintendent Eric Mackey received calls complaining about Black History Month, which the callers conflated (wrongly) with Critical Race Theory.

One of the driving reasons CRT quickly became a hot topic is the fearful claim that schools are teaching it to sow racial discord, and legislation has already been brought forward (and passed in some states) to curb its alleged presence in schools.

Edweek.com writes, "Since January 2021, 36 states have introduced bills or taken other steps that would restrict teaching critical race theory or limit how teachers can discuss racism and sexism, according to an Educational Week analysis." This article also includes a table breaking down the varying language of each piece of legislation; some wording mentions CRT by name, some does not.

In a recent interview, Richard Delgado, a professor at the University of Alabama School of Law and a leading figure in the field of Critical Race Theory, suggests that certain legislation banning CRT is "completely unconstitutional," and that Critical Race Theory is being used as a name for "everything [its detractors] love to hate."

However, even with a basic understanding of what Critical Race Theory is, it is clear that these rhetorical, political, and legislative attacks have very little to do with the content of CRT itself.

Rather, CRT became shorthand for any teaching of United States history that is willing to ask whether genocide, racial slavery, and segregation might have lasting effects on our current politics.

What isn't Critical Race Theory?

CRT itself is not history per se but rather a fairly narrow lens of legal scholarship. It is as absurd to suggest that CRT is being taught in middle or high schools as it is to suggest these same students are being taught quantum physics.

So, are politicians calling for the banning of CRT because they earnestly think public school students are taught the same material as Harvard law students?

An in-depth explanation of these politicians' motivations deserves its own separate post. But in this post, I want to go over what CRT is and isn't, and what relevance it may have to public school curriculums.

To be sure, the questions and problems that CRT poses can be applied to the creation of public-school curriculums. While CRT is not synonymous with historical studies, it certainly sits side-by-side with rigorous work on the history of race in the U.S.

For example, CRT is sometimes associated with the 1619 Project. While they may share the goal of investigating the role of race in the U.S., the 1619 Project is a historical project, whereas CRT deals primarily with the law.

What is Critical Race Theory?

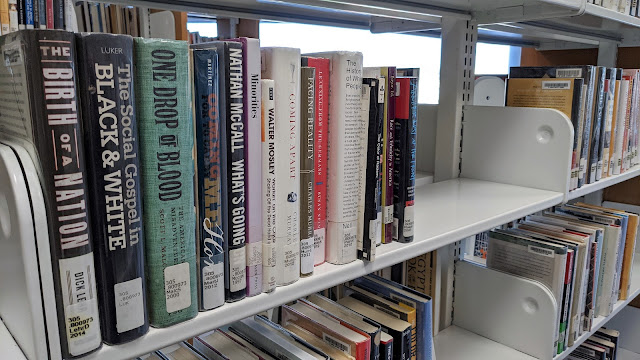

|

| Find these books at the Birmingham Public Library! Photo by Parker Evans. |

To start with the history of Critical Race Theory, we must understand that it stands within a long tradition of scholarship on race that generally begins with W. E. B. Du Bois and other black thinkers, who emerged after Reconstruction.

Du Bois' own book on Reconstruction, Black Reconstruction, remains a classic, authoritative source on the subject.

This scholarship spans multiple academic disciplines, including:

- sociology

- history

- philosophy

- political theory

- gender studies

- legal studies

- economics

And more importantly, CRT refers to a very specific body of work. Strictly speaking, CRT is a branch of legal scholarship that grew out of a larger movement of critical legal studies.

CRT was meant specifically to address the shortcoming of racial analysis in critical legal theory, which contends that the inherent social bias of the law must be an object of legal studies.

Even in more receptive circles than Governor Ivey's, CRT is often ascribed a greater breadth than it has aspired to. Perhaps that is because the implications of CRT are themselves so far-reaching.

The premises of CRT, loosely speaking, might be summed up like so:

- Race is not a biological reality but a social reality.

- Racial boundaries are constructed and re-constructed over time by material conditions, like slavery, segregation, and institutionalized discrimination, such that legal and economic power tends to consolidate around white people.

- Legal institutions and economic conditions of the United States are some instruments by which these conditions are codified and normalized.

These arguments turn the popular conception of race in U.S. politics upside down.

The common approach to race goes something like this:

The U.S. strives to be the land of equality and opportunity, but race is a particular problem that has not been solved. We will slowly become more tolerant of our differences, and we will progress toward our higher ideals.

What CRT suggests is:

What if race is not a particular problem to be solved—where certain “racists” can be brought to justice—but is in fact baked into the very foundations of our political imagination and institutions?

It is crucial to understand that CRT approaches racism as a problem of power imbalance rather than individual disposition or prejudice.

Racism is not simply a problem of everyone’s individual prejudices that may “go both ways,” but instead it is a description of a social, political, and economic organization that gathers wealth and power around white people and marginalizes people of color.

In other words, CRT argues that the status quo of the U.S. is that white people are the default subjects of both history and the law, and everyone else is secondary unless some special exception is made.

Why is Critical Race Theory relevant?

CRT argues that, rather than approaching race only as an interpersonal problem, it is more productive to approach it as a matter of power regarding the law. If we ask who our legal institutions favor and protect, and why, we get some clearer answers and very challenging follow-up questions.

After briefly reviewing CRT, one can see why some politicians use it as a scare tactic.

Even if said politicians are not actually reading the work of critical race theorists, these theorists' ideas do have challenging and even radical implications:

If race and racism are baked into our social and political structures, then the traditional distinction between "good" white people and "racist" white people starts to make less sense—maybe every white person is guilty and benefits from this structure of power.

But again, this is too simplistic an understanding of CRT.

Terms like “guilt” and “privilege” place emphasis on the individual and not on the systems and institutions with which CRT is concerned.

In this sense, CRT is also a criticism of our legal and political focus on individual actors. If the injustices against black people and other people of color in the United States were dealt out at the multigenerational level, over the course of 500 years, how can “racial justice” ever be delivered one decision or success at a time?

On the other hand, what sort of legal action is even possible to honor, let alone repair, the time and depth of such physical, economic, psychological, and generational violence?

This second question may be overwhelming, but it is not rhetorical. CRT attempts to provide an answer to this question.

As Cornel West writes in the "Forward" to Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement,

Critical Race Theory is a gasp of emancipatory hope that law can serve liberation rather than domination.

If you have even more questions after reading this post, that’s a good thing!

This post is by no means an exhaustive summary of Critical Race Theory, and CRT is only a slice of the larger critical race studies pie.

Academics, activists, and readers like you continue to push the limits of this work by asking questions and seeking answers. Chances are that any question you have was asked by someone before, and the resources available in our library system can help you pursue these questions!

What do I read next?

Putting together a reading list to introduce Critical Race Theory to new readers is a difficult task, mainly because most writings under the label are dense legal articles.

I will include a few texts by authors who fit that label, but this list is closer to a general reading list for critical race studies. This list includes articles, shorter political books, collections of essays, and longer historical books.

Start wherever you like!

More about Critical Race Theory

- “Critical race theory” from Britannica.com

- “A lesson on Critical Race Theory” from the American Bar Association

- “Explainer: What 'critical race theory' means and why it's igniting debate” from Reuters.com

Critical Race Theory

- Critical Race Theory: An Introduction by Richard Delgado

- Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement edited by Kimberlé Crenshaw et al.

- Silent Covenants: Brown v Board of Education and the Unfulfilled Hopes for Racial Reform by Derrick Bell

- Faces at the Bottom of the Well: The Permanence of Racism by Derrick Bell

Essays and Shorter Texts

- The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. Du Bois

- The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin

- Race Matters by Cornel West

- How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America by Kiese Laymon

- Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement by Angela Y. Davis

- How to be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi

- Stay Woke: A People’s Guide to Making All Black Lives Matter by Tehama Lopez Bunyasi and Candis Watts Smith

- The Making of Black Lives Matter: A Brief History of an Idea by Christopher J. Lebron

- Abolition for the People: The Movement for a Future without Policing and Prisons edited by Colin Kaepernick

- Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

- If They Come in the Morning: Voices of Resistance edited by Angela Y. Davis

Testimonies

- River of Blood: American Slavery from the People Who Lived It edited by Richard Cahan et al.

- Remembering Jim Crow: African Americans Tell About Life in the Segregated South

General Histories

- A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn

- The Slave Ship: A Human History by Marcus Rediker

- The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism by Edward E.

- Baptist River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom by Walter Johnson

- The Counter-revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America by Gerald Horne

- Black Reconstruction by W. E. B. Du Bois

- The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein

- The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan and the American Political Tradition by Linda Gordon

- Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement by Barbara Ransby

- Driving While Black: African American Travel and the Road to Civil Rights by Gretchen Sorin

- Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63 by Taylor Branch

- Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963-65 by Taylor Branch

- Bending Toward Justice: The Birmingham Church Bombing that Changed the Course of Civil Rights by Doug Jones

Critical Histories

- The History of White People by Nell Irvin Painter

- How Race Survived U. S. History: From Settlement and Slavery to the Obama Phenomenon by David Roediger

- Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White by David Roediger

- Women, Race and Class by Angela Y. Davis

Comments