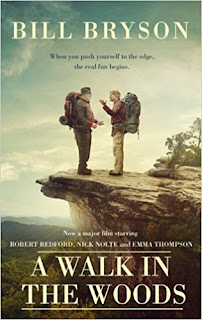

Book Review: A Walk in the Woods

by Richard Grooms, Fiction Department, Central Library

A Walk in the Woods

Bill Bryson

In the mid-1990s Bill Bryson decided on a modest project—he’d walk the Appalachian Trail. Though he didn’t end up doing anything near the whole Trail, he did complete a respectable chunk of it. But first he needed a hiking partner, and of course everybody turned him down, but he did end up with an unlikely candidate, his old Iowa buddy, Stephen Katz, who had major issues and was way overweight and terribly out of shape. Katz would soon become a sort of Sancho Panza to Bryson’s would-be Quixote. The elements of travel and unintentional humor are classic Bryson components and they pay off here in what is probably his best-known book.

Another Bryson essential is facts, the kind you can’t find anywhere else. How else are you going to know that there’s no agreed-upon length for the Appalachian Trail? What is agreed is that it’s the world’s longest footpath and it’s run by the world’s largest volunteer support network.

Katz is the main comic relief of the book:” You know what I look for in a female these days? A heartbeat and a full set of limbs.” Thus Katz breaking the ice with our author. Katz took up Bryson’s hiking offer because he didn’t have any plans, or any real life. But I’ll say this. He put in several hundred miles on the Trail, something that makes a bush league hiker like me refrain.

Bryson admirably shows the importance of wilderness and still mentions that even someone like Henry David Thoreau could be spooked by the Appalachians. A New England portion was suitable for “men nearer of kin to the rocks and wild animals than we.” And Daniel Boone, who, according to Bryson, “not only wrestled bears but tried to date their sisters,” said of the Southern Appalachians that they were “so wild and horrid that it is impossible to behold them without terror.”

Bryson’s background on the Trail might convert even a logging lobbyist. The main thing is that it’s beautiful, of course. As per usual, Bryson’s nature description is welcome reading: “The tunnels of boughed rhododendrons, which often run on for great distances, were exceedingly pretty.” And: “…we were confronted with an arresting prospect—a sudden new world of big, muscular, comparatively craggy mountains, steeped in haze and nudged at the distant margins by moody-looking clouds, at once deeply beckoning and rather awesome.” The combined weight of nature account and argument make a passionate case for the wild.

From the sublime, we move to the squalid. Here’s the author on a less-than satisfactory bed he slept on:” If the mattress stains were anything to go by, a previous user had not so much suffered from incontinence as rejoiced in it.” I count on Bill for that kind of thing.

I was pleased to see that some of the sensations I’ve felt as a walker were echoed and articulated by Bryson. After being in the woods for hours, he sees a car and is stunned by its speed: “Cars shot past very fast—unbelievably fast to us who resided in Foot World.” And there’s the immense, disorienting pleasure you feel when entering a clean, well-lit, air-conditioned store after a hike.

With all these contradictions, you still can see the overall appeal of the Trail. So when Bryson starts to get eco activist, you realize that, if anything, he’s understating it. So “the whole of the Appalachian wilderness below New England could become savanna” is nested in a whole structure of study excerpts. Not mentioned is one that came out after the book which predicts savanna as the future of the entire Southeast by century’s end. All assuming, of course, we don’t change our behavior. It’s sobering and scary, but the beauty of the woods described here can be a great motivator. Bryson isn’t an eco-Puritan, however: “So Gatlinburg is appalling. But that’s OK.” Well, it is appalling to me, but I share with the author, as I said earlier, that pleasure on entering an environment-controlled building after a giant dose of unruly nature. That’s just it: we need them both—wildness and ordered reality.

I hiked small parts of the Appalachian Trail back in the seventies. Bryson makes me want to hike it again. And he makes me want to be an activist for it. Not just any writer can wake me up like that. He’s helped me to understand the deep majesty of these mountains. They’re tied up in our overall American legacy, our Native American heritage, our deep human past and even our pre-human past. They’re unfathomably old and mystery-laden, and this account helps you to get a handle on this.

A Walk in the Woods

Bill Bryson

In the mid-1990s Bill Bryson decided on a modest project—he’d walk the Appalachian Trail. Though he didn’t end up doing anything near the whole Trail, he did complete a respectable chunk of it. But first he needed a hiking partner, and of course everybody turned him down, but he did end up with an unlikely candidate, his old Iowa buddy, Stephen Katz, who had major issues and was way overweight and terribly out of shape. Katz would soon become a sort of Sancho Panza to Bryson’s would-be Quixote. The elements of travel and unintentional humor are classic Bryson components and they pay off here in what is probably his best-known book.

Another Bryson essential is facts, the kind you can’t find anywhere else. How else are you going to know that there’s no agreed-upon length for the Appalachian Trail? What is agreed is that it’s the world’s longest footpath and it’s run by the world’s largest volunteer support network.

Katz is the main comic relief of the book:” You know what I look for in a female these days? A heartbeat and a full set of limbs.” Thus Katz breaking the ice with our author. Katz took up Bryson’s hiking offer because he didn’t have any plans, or any real life. But I’ll say this. He put in several hundred miles on the Trail, something that makes a bush league hiker like me refrain.

Bryson admirably shows the importance of wilderness and still mentions that even someone like Henry David Thoreau could be spooked by the Appalachians. A New England portion was suitable for “men nearer of kin to the rocks and wild animals than we.” And Daniel Boone, who, according to Bryson, “not only wrestled bears but tried to date their sisters,” said of the Southern Appalachians that they were “so wild and horrid that it is impossible to behold them without terror.”

Bryson’s background on the Trail might convert even a logging lobbyist. The main thing is that it’s beautiful, of course. As per usual, Bryson’s nature description is welcome reading: “The tunnels of boughed rhododendrons, which often run on for great distances, were exceedingly pretty.” And: “…we were confronted with an arresting prospect—a sudden new world of big, muscular, comparatively craggy mountains, steeped in haze and nudged at the distant margins by moody-looking clouds, at once deeply beckoning and rather awesome.” The combined weight of nature account and argument make a passionate case for the wild.

From the sublime, we move to the squalid. Here’s the author on a less-than satisfactory bed he slept on:” If the mattress stains were anything to go by, a previous user had not so much suffered from incontinence as rejoiced in it.” I count on Bill for that kind of thing.

I was pleased to see that some of the sensations I’ve felt as a walker were echoed and articulated by Bryson. After being in the woods for hours, he sees a car and is stunned by its speed: “Cars shot past very fast—unbelievably fast to us who resided in Foot World.” And there’s the immense, disorienting pleasure you feel when entering a clean, well-lit, air-conditioned store after a hike.

With all these contradictions, you still can see the overall appeal of the Trail. So when Bryson starts to get eco activist, you realize that, if anything, he’s understating it. So “the whole of the Appalachian wilderness below New England could become savanna” is nested in a whole structure of study excerpts. Not mentioned is one that came out after the book which predicts savanna as the future of the entire Southeast by century’s end. All assuming, of course, we don’t change our behavior. It’s sobering and scary, but the beauty of the woods described here can be a great motivator. Bryson isn’t an eco-Puritan, however: “So Gatlinburg is appalling. But that’s OK.” Well, it is appalling to me, but I share with the author, as I said earlier, that pleasure on entering an environment-controlled building after a giant dose of unruly nature. That’s just it: we need them both—wildness and ordered reality.

I hiked small parts of the Appalachian Trail back in the seventies. Bryson makes me want to hike it again. And he makes me want to be an activist for it. Not just any writer can wake me up like that. He’s helped me to understand the deep majesty of these mountains. They’re tied up in our overall American legacy, our Native American heritage, our deep human past and even our pre-human past. They’re unfathomably old and mystery-laden, and this account helps you to get a handle on this.

Comments